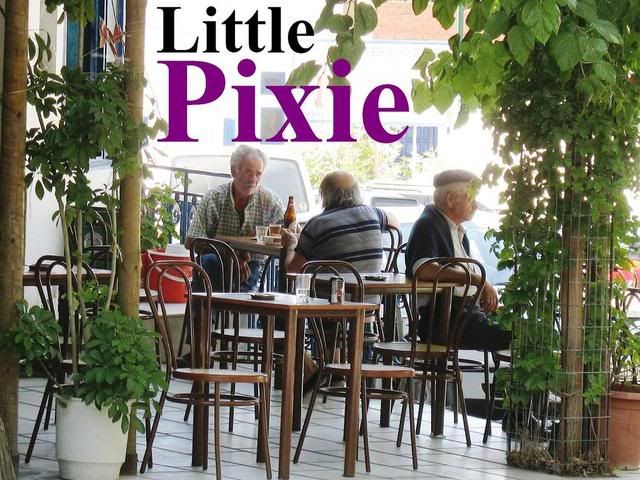

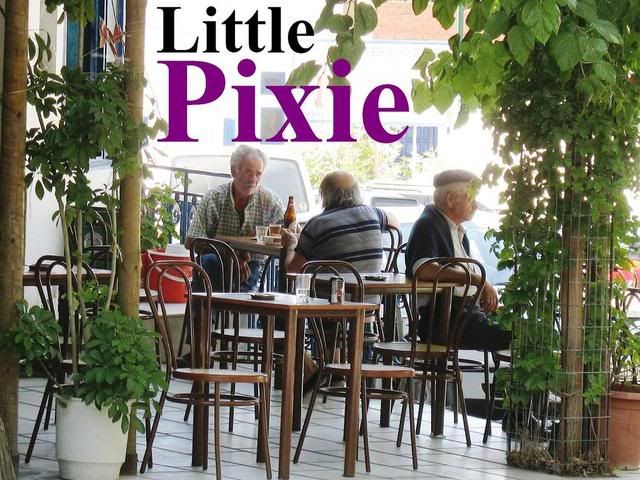

When Thomas arrived at his usual place on the café terrace, he still hadn’t decided whether to say anything to the others about the death of his wife.

Why didn’t I ever bring her here? Would it have been such a big effort? My darling, impossible Valerie. Barely able to keep a hold of his frosted-up glass of beer, he sat down opposite Paul and forced a smile. He also acknowledged Bernard, at the next table, with a clipped wave. ‘Nice day for it,’ he said. Some bold sparrows skipped from table to table, attacking plates not yet cleared away.

Don’t need to worry about us oldies, eh? Too slow now to be a threat. ‘Nice day for what?’ asked Paul. He had both hands spread around his drink, as if he were hoping for some heat, with his book, keys and cigarettes neatly lined up in front of him.

Thomas sighed.

Everything tidy. Everything in its place. He saw that Paul’s long grey hair remained unbrushed and greasy.

Forget the tidy piles, my friend; you need to look after yourself. ‘See? You can’t answer,’ said Paul. ‘Just another silly expression people use.’

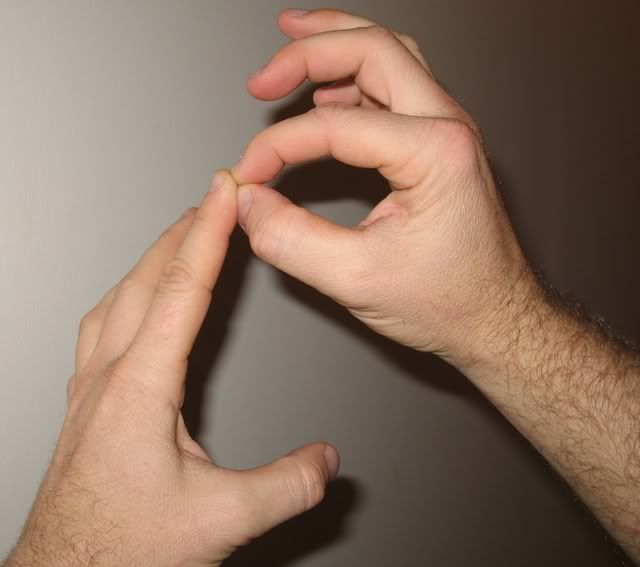

‘Well, nice day for a beer is the first thing that comes to mind,’ said Thomas. ‘A nice, cold beer in the sun.’ After taking a generous mouthful, letting it rush down in one go, he clasped his hands and let them rest on his belly. His wedding ring glistened in the sun.

Was it the second or the third Saturday in August, 1952? Who would’ve thought, eh? All that time together. I always said she’d go first, though. ‘Don’t need nice weather to enjoy a beer,’ said Paul.

Thomas couldn’t help but feel regret for all those days he’d left Valerie at home.

What else did she do, except fuss over household jobs that hadn’t really been necessary for years? He knew that at some point he would have to phone a list of distant people and tell them the news.

Perhaps tomorrow. Perhaps in a week. And is it better to say "died" or "passed away"? ‘Paul’s gone all moody because he lost a big whack on the horses,’ said Bernard. He turned on his mischievous look: the little-boy-grin, the gyrating of his chin, his green eyes lost among wavy skin and a silver fringe.

‘The figures were all over the place!’ said Paul. He hunched further over his drink, his nose almost touching the beer. ‘Earlier bloody wins and losses weren’t right. How can I calculate things with dodgy figures?’

Nearby, council workers fought with the remains of the morning market, hosing away the shards of ice that still stunk of fish, scraping up rotten bits of cabbage and cauliflower. Thomas didn't think it was right that the sky hadn't turned grey.

How can it remain so bright and still after such an awful event? He wanted to say something about Valerie. He really did.

But how does someone just bring up something like that, all of a sudden, in front of men like this? After a few minutes of silence Bernard said, ‘Where’ve you been the last few days anyway, Thomas?’

Paul nodded and frowned. ‘Yeah, where have you been?’

Thomas thought for a moment. ‘Been having a bit of a time.’ He crushed some leaves about his feet, this time scaring away some of the sparrows.

‘Don’t tell me you’ve found a woman,’ said Paul. ‘You cunning old devil!’

Thomas put his finger on the lip of his glass and made slow circles. ‘I’m a married man.’

‘Oh, yeah, that's right,’ said Paul. ‘Veronica, isn’t it?’

‘My little pixie,’ said Thomas. He quickly put his beer up to his lips, surprised he’d let those words slip out.

That was just our secret. Not just for anyone to hear. He then heard Valerie’s light voice calling him her “unicorn” for the very first time.

The pixie and the unicorn.

Bernard rolled a cigarette, folding his legs and leaning forward. ‘Little pixie?’ He squinted, suppressing a smile. ‘I don’t think we’ve had the pleasure.’

‘No, I don’t think you have,’ said Thomas.

The spray from the hose came close to the terrace. One of the council workers yelled out, ‘I can refill your drinks if you want! Hold them steady.’

The three men waved and nodded. 'Best to humour him,' said Bernard. 'Poor fellow obviously wasn’t the sprightliest of the litter, coming up with the same joke every Saturday.'

Paul put on an exaggerated frown. ‘You know what, Thomas? It’s not our fault if you never bring your wife along.’

‘I don’t think he said it

was our fault,’ said Bernard. He pretended to hit Paul on the back of the head.

Thomas avoided Paul’s gaze. ‘Funny, because I was thinking about that just this morning.’ He downed the rest of his beer in one go. ‘I don’t know why I never considered bringing her along ... and it’s Valerie, by the way.’

Paul slouched back in his chair, his eyes looking red and tired. ‘I knew it started with a V.’

Bernard spat out slightly to get some tobacco off his bottom lip. ‘Better off without the ladies anyway. Better left at home, I say.’

Thomas took off his cardigan, gently touching the leather patches that Valerie had put on the elbows just a few weeks before. He’d worn it to the service that morning, on the other side of the city.

Why buy a dark suit just for one day? Valerie would’ve been against it. Anyway, she loved this cardigan, having mended it so many times. He hadn’t chosen the church. He hadn’t chosen anything. Valerie’s sister, Ann, had become the efficient organiser. She'd started crying, though, when he told her that he wouldn’t be staying for the reception after the service. But he didn’t care any more about her tears; Valerie was no longer there to make him apologise. He'd ended up lying, telling Ann that his own friends had organised their own reception in his wife’s honour.

‘How long have we been friends?’ asked Thomas.

Is “friends” really the right word, considering the circumstances? He stood up and signalled to the barman that he wanted another beer. His legs felt like slabs of stone.

‘Not all that long,’ said Bernard. ‘You’ve only been here a couple of years, haven’t you?’

‘Must be three,’ said Paul. ‘You came the year we got our kitchen done.’

Bernard took a hold of Paul’s ear. ‘Never seen your bloody kitchen. You go on about it, but we’ve never actually seen it.’

Thomas slumped down onto his seat again and folded his arms. ‘Suppose I should’ve introduced you to Valerie. Just didn’t think it was urgent. Seems like only yesterday we moved here.’

Paul patted him on the shoulder. ‘Don’t worry. Retirement is a full-time job. Everything in its own time.’

The young barman arrived with the beer. ‘How are things with you lot then?’

‘Could be better,’ said Thomas.

The barman walked on, pushing in chairs and taking away some of the dirty plates. ‘You’re not going to start complaining are you?’

Thomas shook his head. ‘No, that wouldn’t do, would it?’

Bernard and Paul spotted one of their friends from the Irish dancing club. They seemed to come to life as they moved off over the road to greet him, putting on Irish accents, hitting each other on the back. They admired their friend’s new car, a Buick Electra, imported from the States, according to the talk in the pub.

Now that’s a car Valerie would’ve loved. Something she never got the chance to ride in. After finishing his beer in three quick gulps, Thomas decided to leave. He felt sick when he thought about the task that lay ahead: he’d bought large plastic rubbish bags to pack up Valerie’s clothes. The woman from the charity shop had insisted that she would take everything, as long as they were clean, but Thomas knew that Valerie would never have left any dirty clothes in the cupboards. He pictured her standing there complaining about the way he always left his clothes around the house. He didn’t want to cry, not there on the terrace, not in front of the boys, so he made for the exit on the other side of the café.

‘Tell them I’ll see them next week,’ he told the barman.

‘You haven’t had your lunch yet, Thomas.’

‘No. Having lunch with the wife today. Too much time in here has gone and made her all lonely.’

The barman nodded, looking confused. ‘Didn’t even know you had a wife.’

Thomas stepped out into the street and put his head down to avoid the direct sunlight. ‘You and me both, my friend.’

The unicorn forgot about his little pixie. On the walk back to the flat, his tears made it almost impossible to see the way. He had to stop on a bench at one point, overcome with the realisation that Valerie wouldn’t be there with a cheerful greeting when he walked in the door. He sat there for hours, just simply observing all of the couples, young and old, hurrying past.

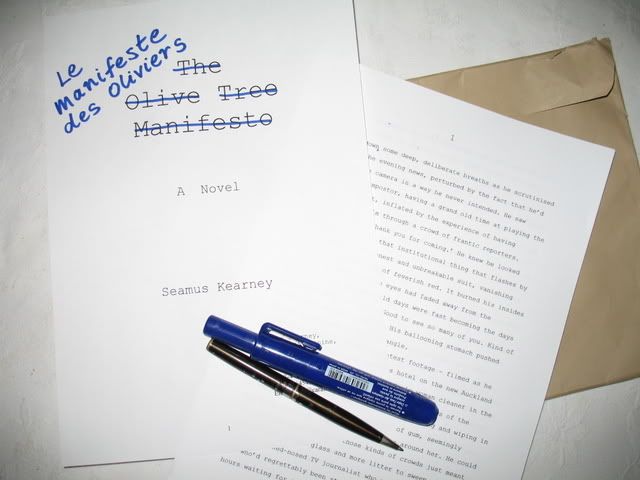

© Copyright, 2007. Seamus Kearney. "Little Pixie"