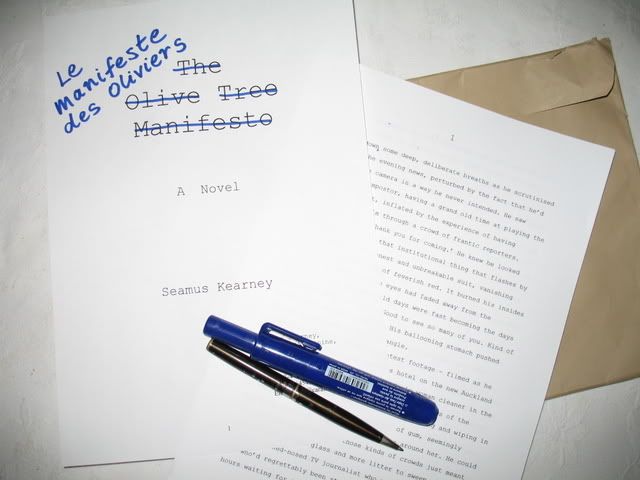

The Cry Of The Peacocks

When our family and friends back on shore started waving at us – slow, sad gestures from the older ones, a joyous scrubbing of the air from the younger ones – I couldn’t help but notice that Tom didn’t join me in waving back at them. He pretended to be busy fastening something down on the side of the boat, with that shirty face he puts on when he thinks he’s surrounded by complete incompetence. I had to wave for the both of us, mouthing ‘I love yous’ - and hoping that Tom’s mother didn’t think they were meant for her. Before we became just specks on the sea, I finished off my farewell by standing up tall and waving my white handkerchief, just as I'd threatened to do. I'd joked that I would do it in theatrical fashion, like a stuffy governor’s wife embarking on an exotic journey to Africa, to a lavish home and tea farm, where servants would rush around to make the stay as bearable as possible.

Tom’s behaviour increasingly worried me. He didn’t smile at my antics with the handkerchief, choosing instead to go inside the cabin and join the posse of four men from the Department of Nature Reserves. They were rough, dour men, there to make sure we settled in to our new posting without any disagreeable surprises. Tom pretended to be busy with plans spread out over a table when I announced with enthusiasm that I would make coffee and heat up a quiche we’d been given. He didn’t even look at me.

‘We’re on our way,’ I said, close up to his ear. ‘No going back. I’m okay about it. I promise.’

He nodded without expression and then gazed out over the waves, perhaps worried that one of the men would overhear me. His dark curls looked duller than usual, his face grey.

‘Don’t worry, I’ll stay overly enthusiastic,’ I said. I went down into the small kitchen, confused about his moodiness.

The trip proved to be speedier than I thought. Before I even had the chance to think about how I could soothe my sea sickness, I caught sight of ropes flying across the porthole and the boat bouncing up against old tyres on the side of a frail-looking jetty. When I came up from down below my attention was immediately seized by the Victorian-style mansion house we’d been told about. Set a short distance back from a sandy beach, the two-storey wooden house had a picket fence out front; a cupola high up on the main roof; and glorious, intricately designed terraces wrapped around the house on both levels. Clouds gathered across the sky, blocking out the sun we'd enjoyed since our departure, but the colours of the sea, the house and the greenery on land remained rich.

‘Looks like your kind of house, Rebecca,’ said one of the men.

I put both hands up over my mouth. ‘All of that just for the two of us?’

‘Well, until you get the visitors coming back for summer tours.’

I didn’t need to be reminded. Part of my mission was to get the place ready for the resumption of day trips from the mainland. Someone from the department had talked about the possibility that I could organise coffee and muffins; put up displays to explain the island’s history; clean up after years of neglect; rearrange the antique furniture; maybe even sand down and revarnish some of the walls. The previous ranger had been a single man - apparently an alcoholic who preferred to live as far away from other people as possible - and he'd been too busy conserving and protecting animals and plants to be worried about the state of the decaying homestead. His retirement had opened the way for something new: a husband and wife team that could magic up a new showpiece for the department.

I didn’t need to be reminded. Part of my mission was to get the place ready for the resumption of day trips from the mainland. Someone from the department had talked about the possibility that I could organise coffee and muffins; put up displays to explain the island’s history; clean up after years of neglect; rearrange the antique furniture; maybe even sand down and revarnish some of the walls. The previous ranger had been a single man - apparently an alcoholic who preferred to live as far away from other people as possible - and he'd been too busy conserving and protecting animals and plants to be worried about the state of the decaying homestead. His retirement had opened the way for something new: a husband and wife team that could magic up a new showpiece for the department.

‘Used to be a house fit for royal visits,’ said one of the other men. ‘I’m told there are 12 rooms in total, each with a different style and theme. Dusty now though. Probably needs a lot of work.’

Tom didn’t seem to be taken by the house. His eyes seemed to be focused on the dense forest that provided an overwhelming backdrop. Some palm trees close to the beach looked as if they were acting as gatekeepers for the wild belt of native and exotic trees behind. With every passing minute the clouds seemed to be coming in lower, almost covering the giant trees at the top of the hills around the bay. We all had to put on jackets.

‘House looks out of place,’ said Tom. ‘But I don’t suppose discreet was their strong point back then.’

‘Well, it’s home now,’ I said. ‘No point wishing it was something else.’

He looked at me with accusing eyes, like I’d said something wrong in front of the others.

I walked down the jetty and leapt onto the sand, leaving the men to unload the boxes and bags we’d brought with us - just a tiny selection of our things. Tom had only signed a contract for one year, to see how things went, to find out whether this specialised island work was what he had in mind.

I first noticed the peacocks when I took a small, sandy path up onto the lawn in front of the house. There seemed to be at least a dozen of them, some sauntering along with their heads pushed back, others chasing one another like excited children. The overgrown garden seemed to provide the perfect playground. I then recalled the little snippets we’d been told about the place.

The house had been built in the mid 1800s by a Scottish architect who’d bought the island for a pittance. He’d imported zebras, wallabies, deer, monkeys and peacocks - not to mention hundreds of foreign trees and plants - with the aim of creating his own “little paradise”. The island passed from one rich family to another and then eventually to the state, which ended up deciding to create a nature reserve. Sadly, the monkeys and the others didn’t fit in; too many native trees and creatures had been destroyed. The peacocks and some resilient deer were the only ones to survive a campaign of terrible culling. I still can’t bear to think about the monkeys getting shot.

After a brief inspection of the grounds, I stood outside the house and grinned, wishing the girls could’ve seen me there in front of that awesome homestead. Yes, it’s me! The governor’s wife! It was obvious there was going to be a lot of strenuous work ahead though. The enormity of the task became clear during a hesitant tour of some of the downstairs rooms. The dust was as thick as carpet in some places and the revarnishing looked like it would take years: virtually every surface was made out of wood, probably kauri and rimu. Old plastic sheets covered the majority of the furniture, with cobwebs covering the gaps.

After a brief inspection of the grounds, I stood outside the house and grinned, wishing the girls could’ve seen me there in front of that awesome homestead. Yes, it’s me! The governor’s wife! It was obvious there was going to be a lot of strenuous work ahead though. The enormity of the task became clear during a hesitant tour of some of the downstairs rooms. The dust was as thick as carpet in some places and the revarnishing looked like it would take years: virtually every surface was made out of wood, probably kauri and rimu. Old plastic sheets covered the majority of the furniture, with cobwebs covering the gaps.

At one of the windows, through the grime, I spotted Tom at the end of the jetty, making angry gestures at the other men, apparently over the way the boxes had been stacked up. The men, looking bemused, just shrugged and walked away. The day had now become decidely darker, and I wondered if the clouds were bringing a threat of rain. The valley of trees on the other side of the bay also took on a very unwelcome, almost sinister appearance in the dimmed light, and I couldn't help but think that the chasing away of the sun was not a good start to our new life.

I looked down at Tom again, asking myself why he'd become so hard to decode all of a sudden. For months he’d almost been at the point of getting down on his knees, begging me to reconsider my resistance to living on an island. He’d told me that a single man – or a man whose wife wanted to stay on shore - would have no chance of getting the post. The department was only interested in a couple who could work together. It didn’t want any more single men who would just become lonely, not look after themselves, turn to alcohol. He promised he would make it comfortable, our own little haven. I relented when he told me about the gardens, the peacocks and the mansion house. No more living in run-down, cold department homes. He said we would make regular trips back to the mainland and I would be free to throw parties whenever I wanted. An open invitation would be extended to the girls! In the weeks before our departure, however, he'd become uncommunicative and volatile, almost as though he regretted his decision to take on the post. I'd just put it down to nerves. The stress of having to move.

‘Bloody clowns,’ he said, bursting into the house. ‘They’ve broken the antenna off the top of the radio. Rough as guts.’

‘Was it important?’ I pretended to examine an old sideboard with lovely stained glass panels in the doors.

‘Of course it was! To keep in touch with the outside world.’

‘Oh.’

He folded his arms and looked down at his boots.

‘This will be lovely in here,’ I said. ‘Look at this furniture and all this amazing wood.’

He didn’t look around though. He checked his watch and then headed over to the window, apparently to check on what the men were doing.

‘We’ll get another radio,’ I said.

‘They cost the bloody earth.’

‘Seems to me it’s more than just the radio, Tom. You’ve been a bear with a bad tooth for days. And today ... well, you wouldn’t exactly win the title for Mr Civilization.’

‘Just leave it.’

‘Just leave what?’ I went over to him and tried to read his face, to see whether this was more serious than I thought.

‘Do you not want to be here?’ I asked.

He didn’t move, his hands trapped in his pockets, his shoulders sticking straight up. I took some deep breaths as I tried to assemble my thoughts.

‘You probably don’t want me to be here,’ I said. ‘Scared of it just being us. You and me, and all this work.’

‘Stop the psychological, Rebecca. Won’t change anything.’

He turned and went back outside. Through the window I saw a small gathering of peacocks take fright and sprint away from him. They made a ghastly screeching sound, like something I’d never heard before. Tom kept on towards the jetty, his steps heavy on the grass, his shoulders still hunched up. I stood there staring at the grass for a few minutes, while the peacocks kept up their strange cries. A dark cloud then swallowed up the sky's last little corner of blue.

I did my best to put aside the tension, again trying to convince myself it was probably the stress of the move, saying goodbye to our family and friends. You probably don’t want me to be here. I mounted the stairs to check out the other rooms.

One of the men from the department had told me about the upstairs library, which he said would be the perfect place to organise some displays on the history of the island. He said I would even find some old exhibits that had been put together back in the 70s, complete with black and white photographs and protected in glass cabinets. When I entered the room I could see that the dust was going to be the biggest challenge. Luckily I’d arranged to have the men bring over an industrial vacuum cleaner.

One of the first glass cabinets I found was waist-high, sticking out from beneath an old sheet and facing in towards the wall. I wrapped my foot around one of the legs and pulled it out towards me, so I could see some of the old photographs and pieces of card with small writing on them. I skimmed over what appeared to be general details of the island’s animals and plants; and then something else caught my eye:

The history of the island is not all joyous. A certain Captain Gordon Lambie, who was brought over from England to be the official conservator of the exotic plants and wildlife, was arrested in 1876 over the mysterious disappearance of his wife, Jane Lambie, the daughter of a doctor from Taunton. The young woman’s friends on the mainland had alerted the local constabulary to the fact that they had not heard from Mrs Lambie for several months, which was highly unusual, and the numerous letters they'd since posted to her husband had gone unanswered. When he was eventually questioned, Captain Lambie told an investigating magistrate that he had awoken one day to find his wife missing and had assumed that she had hired a boat and fled their marriage. The constabulary established, however, that no single woman had hired a boat in the entire district over the period in question. The inquiry took on a sense of urgency when a fisherman, who’d anchored his boat in the harbour about 12 weeks after the couple’s arrival on the island, came forward to declare that he’d heard a long and loud argument coming from the mansion house. He also reported that during the night he awoke to the sound of what he thought was a woman screaming for help, but then decided it was nothing more than the loud cries of the famous peacocks. The island was searched by constables but nothing was ever found. Captain Lambie was never charged in connection with the disappearance of his wife, due to a lack of concrete evidence, and he returned to England where he later died of tuberculosis. There was never any trace of Jane Lambie. However, some years later, the investigating magistrate, Arthur Shipton, revealed in some personal papers that he was convinced that Mrs Lambie had indeed been killed at the hands of her husband and her body had been buried somewhere on the island or dumped at sea. He wrote that he based his opinion not only on the testimony of the fisherman who’d been anchored in the bay, but also the testimony of Jane Lambie’s friends, who said that she’d written to them several times to complain about her increasing unhappiness on the island. Mrs Lambie told her friends that the captain had become angry and resentful of the fact that he’d been forced to live alone with her, with no one else to talk to. She also expressed her concern that her husband had developed what she called a kind of “island fever”, and over numerous weeks he became deeply depressed about his “loss of contact with the outside world”. The magistrate finished his diary entry on the subject by saying that he'd been disturbed by Captain Lambie’s “aggressive” behaviour during questioning and his apparent lack of sorrow over the disappearance of his wife. “If only it had been possible to question the peacocks,” he wrote. “Theirs are perhaps the only other eyes who saw the final moments of Jane Lambie’s life.”

Just before dusk - long after reading the disturbing account in the glass cabinet, and after the men had finished all their important electrical and mechanical checks - I saw Tom raise his hand and wave goodbye to the departing boat. He turned around towards the house a few times, probably to see why I hadn’t come down to see the men off. His annoyance was evident in the stilted rhythm of his waving. I looked over towards the palm trees, and the forest that seemed to be creeping closer, and I thought of Jane Lambie. I may’ve been wrong, but I think I also saw some of the peacocks join in with Tom’s waving, their glorious blue and green plumage fanning out in a collective demonstration of farewell and good luck. I can’t be sure though, because just as my eyes started to focus on the peacocks, approaching footsteps up on deck meant I had to quickly pull away from the porthole and hide back under my blanket.

© Copyright, 2007. Seamus Kearney. "The Cry Of The Peacocks"

Photograph of peacock by Adrian Pingstone, England.